Stories

Fashion on the Home Front

1914-1918

Women’s fashion changed constantly at the beginning of the 20th century, and those who had the income and the inclination wore richly decorated clothing that sometimes verged on the extreme. The First World War put an end to the frivolity. Simplicity, practicality and a show of patriotism became the driving factors in fashion.

Although we were a long way from Europe, up to date news of Northern Hemisphere fashions did reach New Zealand. Many provincial newspapers published regular articles which described the details of the latest fashion for a local audience. Writers such as 'Myra' from the Observer, 'Marguerite' from the Otago Witness, 'Mabel and Christabel' from Free Lance and the regular 'London Fashion Notes' column from the New Zealand Herald guided women in their clothing purchases. Readers were also advised what was happening in Paris: "The Panama hat is to give way to the pretty up-turned salon hat …" (Free Lance, 29 March 1902). And also what they might find in their local stores: "Many exquisite frocks of muslin and other ethereal textures are now to be seen at the big draper shops," (Observer, 24 January 1914).

In the early 20th century, the most desirable wardrobes included garments that were feminine and richly embellished. Hats were oversized, blouses had high necks, skirt hems touched the shoes, and corsets were commonly worn.

The 1909 wedding of Mr E C Nahr and Miss Martha Monteith at Reefton complete with oversized hats and richly decorated garments. Photo from Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, NZG-19091124-29-2.

Once the war had begun, decorations such as lace and feathers fell out of favour. "For the time being," wrote Myra, "eccentricities are banished and a check put upon foolish extravagances." In January 1915 she wrote: "The influence of the war on fashion has produced already a marked improvement. The exaggerated, grotesque modes which were once provided for the choice of women have disappeared and in their place come the simple, trim, tailor-made costumes which are so essentially British."

Garment sketches illustrating the sensible simplicity approved of by Myra in her 'Fashions Up-to-date' column for the Observer, 16 January 1915.

Three months later, the loss of life that occurred as a result of the Gallipoli campaign reinforced the seriousness of the war to those at home. This was reflected in dress. Sombre, muted colours took over and showy decoration and jewellery was discarded.

Dressing for active service

Military-influenced embellishment was acceptable, however. Women often wore regimental ribbons or jewellery honouring the men fighting in war.

Ad for ANZAC brooches and pendants in the Dominion newspaper, 1917.

It was also seen as patriotic to adopt aspects of the military uniform, and feminine versions of army overcoats, trench coats and jackets were worn. Garments often featured military-style details such as metallic buttons and buckles, braid, epaulets, pockets and high collars.

One letter to the editor by 'A sister on Active Service' demonstrates a commonly held attitude towards women’s fashion. "Why cannot those of all classes who are really patriotic show a good example by dressing in the plainest and simplest manner, and prove to all they are really on active service?" (Dominion, 24 March 1917)

Followers of fashion were well-informed about the historical importance of their fashion choices. "Tartans have nearly always had a run of special popularity in times of war," wrote the New Zealand Herald, "and this was especially so during the years immediately following the great achievements of the Highland regiments in the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny, Black Watch and Gordon tartans being particular favourites." The same thing was also noticeable after and during the South African war, and it was then, too, that khaki first made its appearance as a woman's colour. (New Zealand Herald, 2 December 1916.)

Khaki, was in favour again for women’s fashion and in 1917 the Observer described two khaki dresses: "an afternoon gown of khaki serge with a wide black moire sash between its pleated skirt and bodice" and "a khaki taffeta frock, gauged and piqued that had effective touches of nattier blue".

Wider skirt styles with a mid-calf hemline were favoured to allow more freedom of movement. High necked garments were also replaced by versions with a softer shoulder and a lower neckline for the same reason.

Two women wearing blouses with a softer shoulder and a lower neckline, 1917. Photo by Mary Frances Mackay, courtesy of Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2007-1-177.

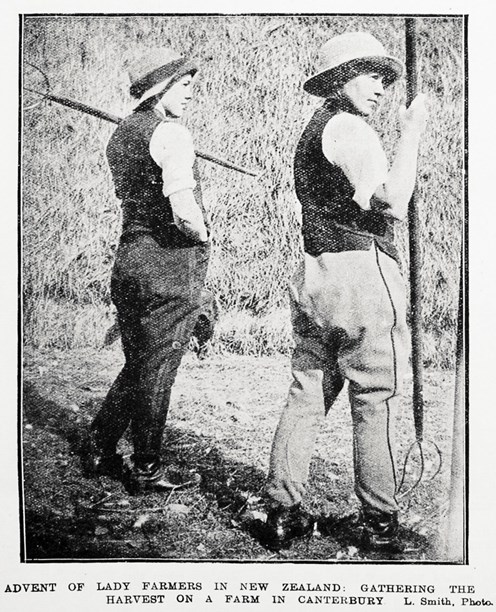

During the war years many women were employed in previously male-dominated roles, such as farming, transport or work in factories. The physicality of this type of work meant that traditionally female garments were often not appropriate. Some women raided men's wardrobes for shirts and trousers to adapt or their skirts were modified to be more practical.

Two women farm workers in Canterbury, 1917. Photo from the Auckland Weekly News, courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19170412-44-5. No known copyright.

If any of the new roles taken on by women required them to wear a uniform, they would happily set their personal fashion preferences aside and wear these to work.

Two women, probably staff at the YMCA Codford Camp, in 1917. Photo by Alexander Douglas Johnston, courtesy of the Masterton Library Archive, 530179.

Making it work

As materials were diverted to war manufacturing, practical and well-made clothing became a priority. Women were also advised to be economical with their purchases. There was plenty of advice from the fashion columnists. "If you can't have many new clothes, be sure that the new things you do buy are right … After all, good dressing is greatly a matter of being appropriate. It is always false economy to buy cheap materials. They do not wear well, and very soon assume that shoddy look which every woman detests." (Observer, 29 January 1916.)

There was advice for remaking and remodelling existing clothing - wearing "last year's" white linen or crepe skirt, for example, with a basque blouse of Japanese silk or embroidery or with a blouse of dainty figured voile or muslin.

Hats could also be re-fashioned. "For once Fashion is kind ... for all the new hats are skillfully composed of odds and ends, such as women carefully preserve in the hope that they will "come in." All the miscellaneous collection of short lengths of straw plait, ribbon, silk, or other material, bead ornaments, faded flowers, etc., will "come in" in this year of grace, and should not be hoarded a minute longer. (Observer, 23 March 1918).

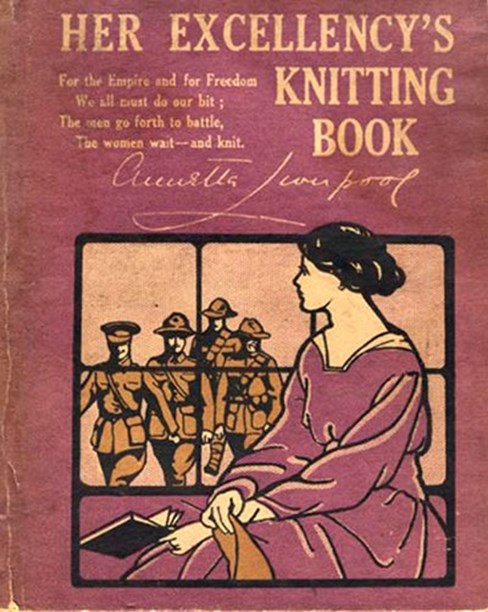

Domestic skills had never been so valued as an essential service. Not only were women encouraged to make, mend and amend their own clothes, but they were also knitting and sewing for the men at war. Not everyone knew how to knit, but knitting patterns and instructions for socks, mittens, slippers and balaclavas were printed in the newspaper. Lady Liverpool, the wife of the Governor General, even published a book of patterns for soldiers, Her Excellency's Knitting Book. Knitting was not only practical but could also be a sociable activity that provided support, both emotional and more practically when groups gathered to prepare and re-work garments before they were sent away.

The cover of this knitting pattern book features a poem: "The men go forth to battle, The women wait – and knit." Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira.

School children, both male and female, were also recruited to this patriotic knitting campaign making scarves and other 'comforts' for the Allied soldiers. All of this knitting however created a shortage of wool, wool which was also needed to manufacture soldier's uniforms. In some areas women began spinning their own wool (Manawatu Times, 17 October 1918).

Fur for all

One material that surprisingly did not face a shortage was fur. Traditionally perceived to be the sole prerogative of the wealthy, during the First World War the fur industry flourished in New Zealand and many women began to wear fur for warmth in the winter. Kathryn Hunter in her article 'Furs in early twentieth-century New Zealand: ecology, war and fashion to the 1930s', (History of Retailing and Consumption, 2019) suggests that the democratisation of furs in New Zealand was linked to a more democratic hunting culture, rather than wealth.

Studio portrait of a woman wearing a fur stole, circa 1917. Photo by Adam Maclay, courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-184575-G.

Mooneys and Madame Menere were two thriving Dunedin furriers, the latter selling new fur garments as well as remodelling existing ones. As the war progressed, fashion columnists passionately promoted fur for winter wear. "Furs are in tremendous evidence. Fur reaches the acme as a trimming," wrote Marguerite in the Otago Witness. "Fur makes the collar or, where not, borders it. Fur makes the cuff or, where not, half of it. And fur embellishes the pockets, and sometimes borders the entire coat. Then fur is used as a material. In other words, it is let in to make panels, etc. As for saying that fur helps in millinery, why waste space stating such a pre-eminent fact?" (8 May 1918).

The popularity of fur can be seen in studio photographs from the era. Dressed in their 'best', women wore fur stoles, capes and coats, or, in the case of women of more modest means, garments trimmed simply with collars and cuffs of fur. Although the price of different species ensured some furs were more exclusive than others, in this era fur became part of the wardrobe for a great many women.

Down on dowdiness

Formal attire didn’t get a lot of wear during this time as social activities were mostly reduced to fundraising for the war effort and the primary focus of fashion commentary was on practical and durable everyday wear. Despite the belief by many that this was no time for showy or conspicuous dress, as the war progressed there was also a growing desire for dressing up and frivolity.

Myra from the Observer describes it as: "Many women have a conviction, to which they firmly cling and indomitably practice, that because of the war it is their duty to let their appearance go, that the pretty things of duress should be resolutely put on one side, that drab dowdiness should in every way be encouraged, because of the war. This idea is all wrong. Because of the sorrow and gloom that this awful war has brought into so many homes it is woman's most particular duty to keep the world as pleasant-looking a place as possible." (23 February 1918)

Queen Carnivals were one patriotic solution to the desire for pretty things. They were held throughout New Zealand to raise funds for war-related causes, such as support for wounded soldiers who were returning home. In addition to talent shows, fancy dress and sporting fixtures, women competed to be Queen. The winner was crowned at the end of the carnival as a reward not just for costuming, but also for their success in gaining community support and funds for the cause.

Lace dress was worn by the winner of the Queens Carnival in Timaru in 1915. All Rights Reserved, image © Kathryn Wycherly.

Weddings would normally be another opportunity to wear more celebratory clothing, but with men often marrying before they left to fight, wartime wedding dresses were often undecorated, reflecting the seriousness of the occasion. The Observer (27 July 1918) reported: "At most of the recent weddings the principal feature has been the simplicity of the bride's outfit. Simple muslin or net frocks are worn, and plain tulle or net veils." Neat travelling suits were sometimes worn in preference to the white wedding dress.

The aftermath

It took until halfway through 1919 before fashion re-emerged, albeit in a more relaxed style. "After four years or more of war conditions we have almost forgotten what an evening gown is like, and there will be ample scope for the designers to show their skill during the next year or two." (Observer, 7 June 1919). Even hairstyles weren’t exempt from the excitement of life in peace time. The 'bobbed coiffure' was introduced by the war-worker who found that the care of long hair took up too much time. Once life became less strenuous, "novelty" hair styles began to appear.

World War One was a catalyst that led to emancipation in women’s dress, which was now less constraining and allowed freedom of movement for a physically active life. Many were reluctant to forfeit their new-found freedom, their independence and autonomy and continued to work 'outside' of the home. For them life and fashion would never be the same again.

Text by Kelly Dix. Banner photo of John Frederick Taylor and Maud Florence MacLeod (nee des Forges), 15 February 1917, Wellington, by Berry & Co. Purchased 1998 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds. Te Papa (B.045853)

Published July 2020.