Stories

Fashion by Decree

1940-1945

In September 1939, when Britain declared it was at war with Germany, New Zealand followed within hours. The escalation of hostilities over a five-year period led to shortages, clothes rationing and fashion by government order. We were obliged to make do, buy wisely and buy less.

The seriousness of the clothing situation wasn’t immediately apparent. Throughout 1940, the major department stores continued to advertise fashion with all the frills. Milne & Choyce in Auckland offered stylish floral silk matching turbans and dresses with flared skirts and ruched detail, John Court’s featured lavishly trimmed georgette blouses, and the DIC in Dunedin proudly promoted luxuriously decorated hats. Evening dresses, made with copious amounts of material, appeared in an advertisement for James Smith’s in Wellington as late as 1941.

James Smith’s evening dress advertisement. Wellington Evening Post, 1941.

At the outbreak of war, fashion-conscious New Zealand women wore pure silk stockings. Nylons, which debuted at the World’s Fairs in New York and San Francisco in 1939, and ceased production in 1942 due to nylon being commandeered for war use, didn’t arrive here until the end of the decade. Anticipating a shortage, women began stock-piling silk stockings in 1941. This prompted a plea from Prestige, one of the country’s major producers of fully-fashioned, seamed silk hosiery, to show some restraint and not to panic-buy. Even with 40 per cent of their staff overseas on active service, they promised production would continue. In April 1942 the New Zealand government provided the solution. Stockings were the first item of clothing to be rationed – one pair per person every three months.

After Japan, a main source of raw silk, entered the war in December 1942, supplies dwindled and silk stockings did become scarce. Dunedin department store Dreavers introduced a weekly stocking-repair service and the makers of Lux Flakes claimed stockings washed, using their product, would last longer.

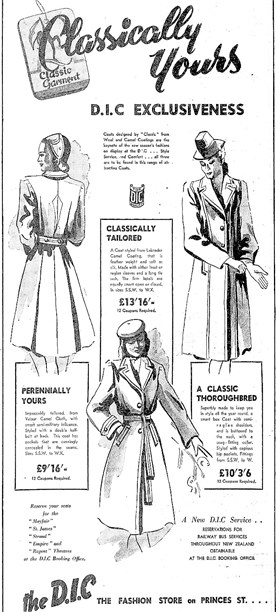

Full rationing, which came into force in May 1942, included clothing, footwear, fabrics and woollen yarns. Each item required a certain number of coupons and 52 clothing coupons a year were allocated to each household. The DIC in Dunedin reminded customers: "When to town you wend your way, Carry your ration book each day." The government also imposed austerity measures on clothing manufacture. To reduce the amount of fabric used, yardages were specified for each type of garment. Superfluities, such as tucking, shirring and pleats, were banned and the number of pockets and buttons regulated. Inspectors visited clothing manufacturers on a regular basis to ensure the rules were being followed.

Twelve coupons were required to purchase this brushed fleece coat from the DIC, Dunedin. Evening Star, 1944.

Possibly because they used very little material and boosted morale, hats escaped rationing. Pillboxes, trilbies, tams and other small neat shapes defined the war-time style. As fancy trims were in short supply, for the most part hats were unadorned and often worn at a rakish angle, tilted forward or to one side.

War-time chic. Pillbox hat photographed by Clifton Firth, 1940s. Image courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-M7B1.

The plain print dress became the unofficial daytime uniform. The epitome of utilitarian trimness, what it lacked in detail it made up for in cheerful colours and exuberant prints. The shape didn’t differ much but there were subtle variations, the 'apron' frock, for example, which had a front panel, patch pockets and a tie-back reminiscent of an apron.

A trio of print day dresses by Classic Manufacturing photographed by Clifton Firth in 1941. Photo courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-CLA-13.

If made from a quality woollen fabric, a coat, an essential in every woman’s wardrobe, would last for years. Because of the restricted yardage, there were two basic styles – the belted coat and the box coat, described as 'the coat to wear over a tailored suit'. Double-breasted styles were banned as were extraneous details. It was quite literally a case of cutting one’s coat according to one’s cloth.

Department stores rarely mentioned labels but the coats in this DIC advertisement are identified as being made by Classic Manufacturing. Evening Star, Dunedin, 1944.

The fur coat (15 coupons) was another long-term investment. Furriers such as Mooneys had their own salons and showrooms and also sold through major department stores like the DIC and Milne & Choyce. New Zealand coney (rabbit) was used a lot as it was relatively cheap and could be dyed to give the appearance of sable and other more expensive furs.

Full-length fur coat photographed by Clifton Firth for Mooneys Furs, 1940s. Photo courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-M53B.

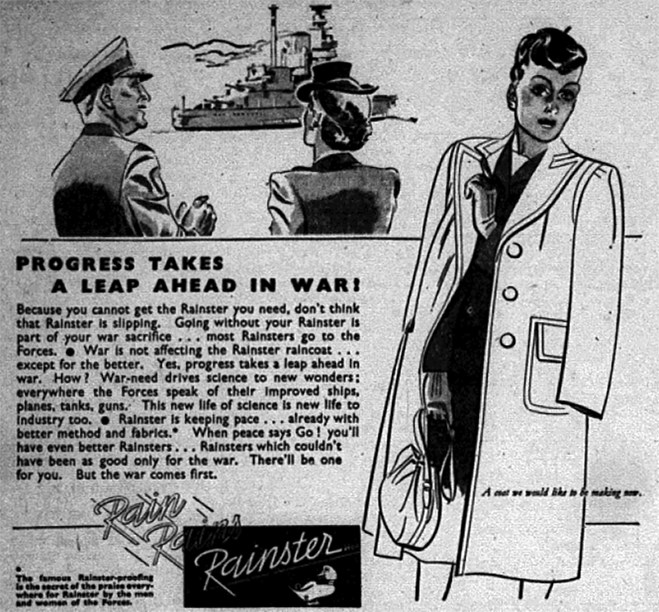

Sadly, Rainsters were a casualty of war for the general population, most of these popular raincoats, for men and women, going to the Armed Forces. That didn’t stop Rainster advertising, though. One heavily patriotic advertisement pictured ‘a coat we would like to be making’ and promised an even better product after the war due to advances in fabric weatherproofing technology. Rainster began production in the 1930s in Auckland and was manufactured by Harris Langton Limited.

Ad for Rainster coats, 1944.

Dress fabrics, although less plentiful, were still available. In 1943, the DSA in Dunedin reported that thanks to the British Navy and the Mercantile Marine, they had just received several shipments of wool and cotton materials from England. Similarly, other department stores around the country were able to replenish their supplies. Purchasers of fabrics and dress patterns from Farmers in Auckland were offered a free cutting-out service, the New Zealand Women’s Weekly provided a free pattern service each week and the Druleigh College of Dressmaking gave lessons on how to remodel old frocks like new.

Aprons were necessary to protect the few dresses women owned. Pattern page from New Zealand Women’s Weekly, January 1940.

While many brides chose to marry in day suits or dresses, others took advantage of the limited supply of evening fabrics and had a traditional white wedding. Typical of the era, were gowns cut on classical lines with gathered shoulders, long sleeves and a train.

For her wedding to William Gilchrist in Dunedin in 1944, Betty Neill wears a white satin gown with a lace train.

As a substitute for silk, Iris, Silknit, MayBelle and other fine lingerie manufacturers resorted to using Celanese, silk-like British fabrics made from an acetate rayon yarn. Lightweight and soft to the touch, they were hard to tell from the real thing. Rendells in Auckland sold Celanese by the yard.

Silknit camisole and knickers with applique trim, 1940s. Photo by Clifton Firth, courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-D270K.

By 1943 there was an acute shortage of rubber, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, the primary producers of 90 per cent of the world’s supply, having fallen to the Japanese the previous year. The corset industry, which was heavily reliant on elastic, was particularly hard hit. Forced to reduce the number of elastic panels, stretchable inserts and suspenders on their corsets, Berlei assured women that, despite the deficiencies, their foundation garments continued to provide good fit and support.

War-time ads for Berlei, 1944.

A woman who was a child during the war recalls her mother knitting her a cardigan, using different-coloured wools left over from other projects. "It was yellow with a garish green and red flower pattern, undoubtedly a work of art but somewhat embarrassing to wear." Knitting wool was rationed to just a few skeins per customer, so it wasn’t unusual for assorted leftovers to be incorporated in one garment or for old woollens to be unravelled and re-knitted in another style.

1940s Paton & Baldwins pattern for a ladies knitted jumper using Patons Beehive wool. Short, fitted jumpers like this one were enormously popular.

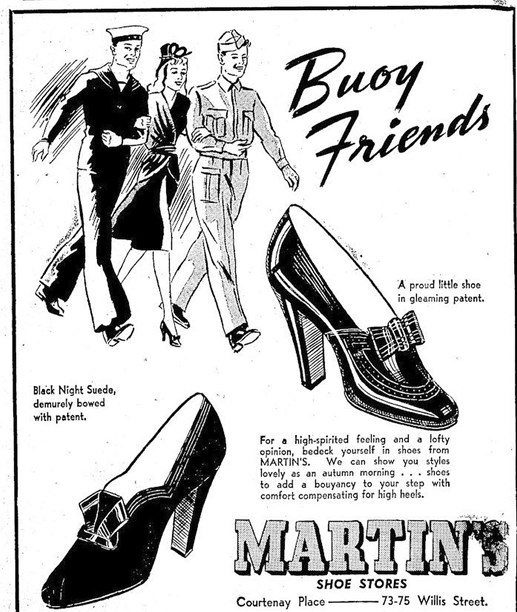

'For Special Mention. Matchless Shoes.' Advertising copywriters and artists frequently used military terminology and imagery to capture the atmosphere of the times. They referred to dress shops as 'suit headquarters', to twinsets as 'gallant' and coats as 'commanding'. Floral house smocks in 'gloom-dispelling colours' were selected 'for service on the home front'.

Morale-boosting advertisement for Martin’s Shoe Store, Wellington. Evening Post, 1944.

American troops, who were to fight in the Pacific war, arrived here in 1942. 20,000 were based in Wellington, 29,000 in Auckland. New Zealanders, seduced by Hollywood glamour and a perceived American way of life, welcomed them with open arms. Auckland dress salons Trilby Yates and Ninette Gowns were among the businesses to benefit from the GIs’ largesse. It was from high-class fashion establishments such as these that GIs bought model gowns for their girlfriends. Mindful of the associative cachet, retailers gave American names to items of women’s clothing, hence the American stroller coat, the Jeep coat, the Yankee jacket and the Johnny Jeep coat, 'the coat that goes with anything - anywhere'. The Mirror magazine featured American fashions modelled by film-stars and, in 1944, Christchurch-based cosmetics and toiletries manufacturer Wilfred Owen (founded in 1938) introduced Screen Star, 'real Hollywood-style makeup that stands a close-up'.

Local girls socialise with American servicemen at a dance held at the Majestic Cabaret, Wellington, 1942. Photo from Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: PAColl-0089-1-06.

The European conflict ended in May 1945, the Pacific war in August. Although clothes rationing lasted until 1947, things slowly began returning to normal. Clothing manufacturers such as Fashions Limited, whose women’s garment output had been greatly reduced due to the fact they were also making service uniforms, were able to resume pre-war production. Nylons arrived in the shops, veiling and flowers reappeared on hats, dresses eventually got their swish back and coats their swing. Reflecting the new optimism, C. Smith’s in Wellington opened a dedicated sportswear department with brightly coloured awnings and stocked it with play-clothes and bare-midriff swimsuits 'for fun in the sun'.

Nylon stocking window, Brown Ewing & Co, Dunedin, late 1940s.

New Zealand fashion didn’t die during the war, it just took a nap. The garment industry, initially slow to respond to the implications of Christian Dior’s New Look (1947), finally recognised their importance. 1940s austerity gave way to 1950s femininity, signalling a return to fashionable elegance for the foreseeable future.

Text by Cecilie Geary. Banner image by Clifton Firth, courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-M7E1.

Published May 2020.