Stories

Fanny Buss

1910-1986 (Fanny Buss), circa 1953-1991 (label)

Her name is on the label of thousands of hand-printed dresses, but Fanny Buss is more than a one-woman band. Although she started printing textiles as a cottage industry as her children grew up, Fanny didn’t start selling clothes until she was in her 50s. Her home-based enterprise flourished and unexpectedly grew into a cooperative fashion and linen label that provided a creative outlet and an income for Fanny and three generations of her family.

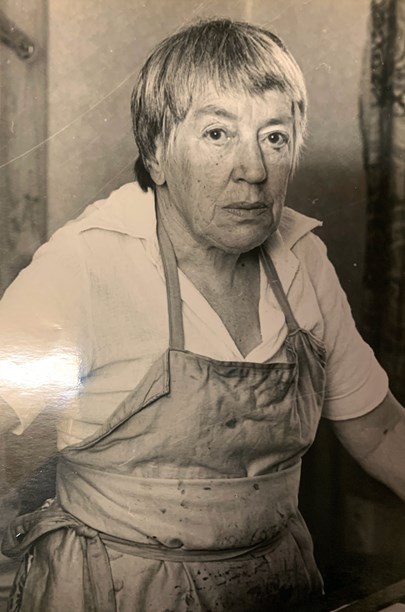

Fanny Buss. Image © Lee Trusttum.

Frances Edith Buss was born in 1910 into a Canterbury farming family, the eldest of four children. Diagnosed with polio (later discovered to be a form of muscular atrophy) she lived in Christchurch after her surgery and treatment and later attended boarding school in Timaru.

In the late 1920s, Fanny enrolled at the Canterbury School of Art. Classes included sculpture, painting, life drawing, still life and landscape. When the Great Depression reduced her family’s income, there was no money for fees, so Fanny left the bedsit she shared with art school friends Rita Angus and Jessie Lloyd and returned home to the farm.

It was here that she met her husband Douglas Cresswell who, having survived the First World War, had found work on the Buss farm. As was the norm at the time, Fanny set aside her work as an artist to raise her four children in Governor's Bay. As her children grew older, Fanny started drawing again. In 1953 she began to print fabric. "She tried different things for her blocks; cutting out lino or spongy Wettex dishcloths and glueing them onto blocks of wood; she cut designs into potatoes with a vegetable knife and also swedes, as they were larger," recalls her youngest daughter Lee Trusttum. "Wood itself was too hard, but much later someone suggested balsa wood, which could be bought in different thicknesses and could easily be carved with a very sharp scalpel. It was too soft to make really fine images but fine enough for her purposes."

Fanny also began screen printing, making her screens herself. Her printed textiles, occasional work as a book illustrator and children’s book writer, provided welcome income for her family.

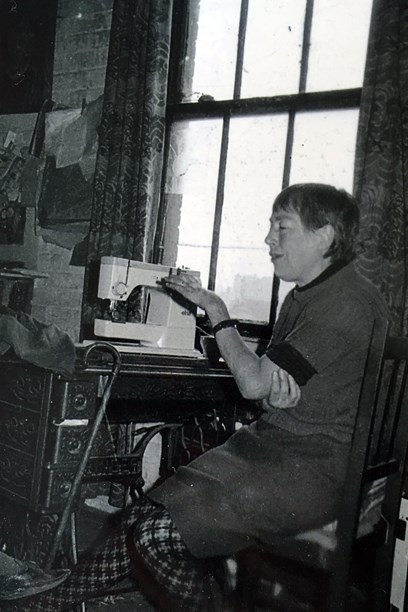

Fanny Buss screen printing in her studio, 1964. Image © Christchurch Star.

To begin with, Fanny printed onto furnishing fabrics. These were often quite a coarse weave so she could unravel the edges to create a fringed finish. These items sold well and were quick to make as they involved very little sewing. At first, Fanny sewed things herself, buying a zig-zag sewing machine to prevent the fringing from further fraying. She made a lot of table mats and zig-zagged around a lot of beach shirts before she found someone to take over that job. These were simple garments; later they would need more experienced dressmakers.

Fanny Buss, 1967. Image © Lee Trusttum.

Always experimenting, she moved on to silk of various weights for dresses and scarves, trying batik before settling on printing or painting directly onto the silk. She also dyed the silk in short lengths (sometimes she tied it first), ironing it dry before cutting out the garment. The pieces were laid flat on the printing table, printed, then draped across a clothes horse to dry. The print was fixed by ironing with a hot iron before being sent to the dressmaker for assembly.

When Douglas died in 1960, Fanny sold their house in Governor’s Bay and moved into a studio above a bakery in Christchurch. She was helped occasionally by Lee and Lee’s art school friend Sally Spence.

Fanny's studio was an open space of about 1200 sq ft above a bakery, which had the advantage of keeping her warm during the winter. Images © Lee Trusttum.

Six years later, she moved the business to a semi-detached house she owned in Conference Street.

In 1967 Lee returned home from Australia where she had lived for several years. She joined Fanny and Sally in their workroom at Conference Street. In about 1975 Fanny’s eldest daughter Kathie moved down from Wellington adding to the Fanny Buss workforce.

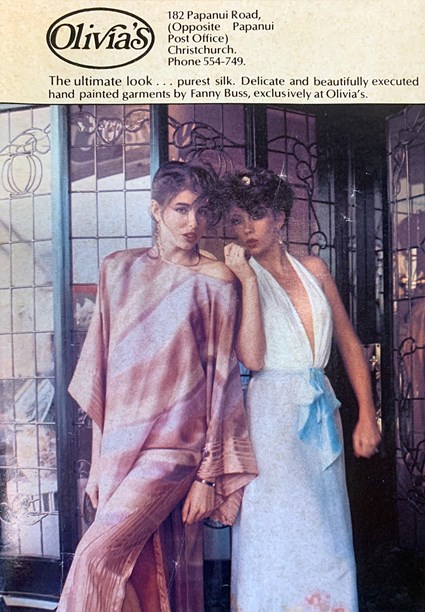

Fanny had been experimenting with different weights and types of imported silk and worked out a method of painting straight onto it that was (fairly) permanent. At this time, she was wholesaling to the New Vision Gallery in Auckland, Dawson’s in Dunedin and Olivia’s dress shop in Christchurch, and she occasionally made wedding dresses to order.

Fanny Buss designs were popular with professional women. One of their most well-known clients was the MP, Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan. Fanny and Lee made many dresses for Whetu, and also printed fabric for Whetu's own fashion studio in Wellington, the Ethnic Art Studio. Lee recalls that Whetu was a wonderful, exciting customer. "When we expressed some reservations about being Pākehā printing Māori motifs, Whetu said we need not worry about that and to just go for it!" (Travel in Style, 2014, p 46).

Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan with Shalima Vuibau (right) and other executive members, at the Māori Women's Welfare League Conference in 1975. Photo by John Miller. Image © John Miller.

In the late 1970s Kathie’s daughter Alexis Watson, who had studied at Elam, joined the collective. "She took to painting on silk like a duck to water, and that rounded off three generations of family enterprise," says her mother.

In 1976 they opened Fanny Buss shop at 20 Papanui Road in the Christchurch suburb of St Albans. For about three years, Fanny, Lee, Kathie and Sally ran it as a collective supported by Marianne Bomer in the shop and by various dressmakers. One of their long-standing dressmakers, Diana Whitby, was a talented hand-sewer and helped out by hand-rolling on hand-painted silk scarves and shawls.

Kathie, Sally, Lee and Fanny in the Fanny Buss shop. Image © Lee Trusttum.

In 1979, the shop moved to Leinster Road in Merivale. Things didn’t go as well as hoped, so the family shut up shop and went back to wholesaling, selling much of their output through Olivia's, also in Merivale.

Ad for Fanny Buss at Olivia's, 1981. Image © Olivia's and Lee Trusttum.

Another Christchurch boutique, Panache, sold a range of Alexis' silk designs alongside the work of Panache owner, Barbara Lee. In 1979, Alexis' silk dresses appeared in a fashion show of Barbara's garments. It was the iridescent quality of silk that attracted Alexis. "When silk is worn and washed it gets a loved look."

Alexis in the Fanny Buss studio at Conference Street in Christchurch, 1979.

After closing the second shop, Kathie, Lee and Sally rented space in the empty teacher's training college where they all painted until the start of 1982. Fanny and Alexis stayed working at Conference Street until, when she was 72, Fanny had a stroke. With Fanny's involvement slowing, Lee's son Martin Trusttum joined the studio. Lee and Martin returned to wood blocking as a technique, and their wood-blocked oversized coats were part of a 'performance parade' and exhibition held at the Canterbury Society of Arts Gallery in 1985. The coats, which Lee described as "one part art, one part fashion" were shown alongside kimonos by Sally and Alexis. The Christchurch Star (14 November 1985) described the garments as "soft sensuous garments with sophisticated use of printing - garments synonymous with the art of Fanny Buss".

Fanny Buss block print coats by Lee and Martin Trusttum, 1985. Image © The Christchurch Star.

When Fanny died four years later, the business split up into separate parts. Although they still worked under the Fanny Buss label, Alexis, Kathie, Sally, Lee and Martin all focused on their own specialties. Although one of Martin's designs was chosen for a Fashion Quarterly editorial in 1989, they eventually closed the business. It had been Fanny who had kept it going.

Text by Kelly Dix. Banner image of Kathie Watson, Sally Spence, Lee Trusttum and Fanny Buss in their studio. Image © Kathie Watson and Lee Trusttum.

Published July 2019.